Selected Works of Fyodor Dostoyevsky ( A Decalogy Set)

₹6,499.00 Original price was: ₹6,499.00.₹5,999.00Current price is: ₹5,999.00.

FREE SHIPMENT FOR ORDER ABOVE Rs.149/- FREE BY REGD. BOOK POST

Read eBook in Mobile APP

Amazon : Buy Link

Flipkart : Buy Link

Kindle : Buy Link

NotNul : Buy Link

In St. Petersburg he kept moving from one address to another all the time as though driven by some secret alarm. He liked to live in corner houses at the point of the intersection of streets where the linear rhythm of the city blocks stumbled to a pause and left empty spaces open to view. He also gave preference to flats from whose windows he could see church domes and spires.

It is a well-known fact that Dostoyevsky was extremely mistrustful and nervous about his health; according to his doctor, he usually drank warm water instead of tea, he worried about his pulse if, to his horror, he gulped some flower tea, and we cannot help smiling as we read this, knowing of his later addiction to the blackest tea and the strongest coffee. For fear that his sleep might be lethargic (a fear he had in common with Gogol), he left warnings in writing before going to bed; he scrutinized his tongue every day and was always on the alert to the slightest malfunctions of his organism. He was quite childishly curious about the shape of his skull which, people say, resembled that of Socrates.

He had his first fit of epilepsy in Siberia. However, he had been subject to sick nervous disorders long before, and they might have been diagnosed as danger signals of the approaching illness. On the other hand they may have been caused by his presentiment of the imminent disaster…

Mikhail Petrashevsky’s “Fridays” were attended by young intellectuals who championed the ideas of Fourier. Dostoyevsky did not come regularly, but he was keenly interested. These gatherings took on a more radical character in 1848, influenced by the revolution which broke out in Europe. They were like the meetings of a political club now–with an agenda, readings, tub no discussions on censorship and the desirable abolishment of serfdom, and even had a bronze bell, rung to subdue the parliamentary passions running too high (this bell proved to be especially indictable afterwards).

The men attending the meeting were arrested on the night of April 23rd, 1849.

Later, when giving evidence, Petrashevsky called it “a case of intentions”. To be sure, unlike the Decembrists, they did not have an organized secret society, and made no attempts to come out in an armed protest. On the whole, their activity did not go beyond talk. The only serious indictment against Dostoyevsky could have been his belonging to the secret group of “seven who were planning to acquire a printing press for publishing illegal literature. However, Dostoyevsky’s participation in this scheme remained undiscovered by the prosecutors. (“A whole plot wasted,” he was to say afterwards). The government, however, had evidence enough without that.

Dostoyevsky was sentenced to death for reading at one of the Petrashevsky group meetings the famous and clandestinely circulated letter from Belinsky to Gogol in which he exposed the deadening system of Nicholas the First’s despotism. The police agent who had wormed his way into the circle had only this charge to bring against Dostoyevsky.

Dostoyevsky spent exactly eight months in a solitary cell of the Alexei Ravelin in the St. Peter and St. Paul Fortress. His speech in self-defence was constructed carefully and, we might even say, artistically. He said he was guilty only of unforgivable mindlessness, but definitely not of belonging to any political opposition. He did his utmost to exonerate his friends: the protocols of the interrogations that have come down to us bear testimony of his courageous and unequal struggle. A more general question arises here: how did Dostoyevsky conduct himself in a crisis, in critical moments of his life, in those almost hopeless situations in which he is so fond of placing his heroes?

He conducted himself honourably.

He could fall prey to obsessive fears, he could be tormented by doubt; he could waver, be inconsistent, and contradict him-self. He could make an endless plaint against his circumstances, blame these circumstances on himself and others, suffer from his mistrustfulness, and make strange decisions. He really had all these shortcomings in a lesser or greater measure, and it would be absurd to deny it.

But that was only until the moment came. When tragedy struck, his personality instantly asserted itself. Disaster was that magician’s trick which united the dissociated elements of his character into one clearly defined personality.

The trial of the Petrashevsky group was one such instance.

The strength that had united him in misfortune never waned in him. Without manifesting itself as powerfully as in fateful moments it paved a way for itself through the thick of petty mundane troubles, as if keeping his personality within its invisible framework.

The “human touch” may seem a bit too much here. But for an artist like Dostoyevsky nothing that was human could be “too much”. In the usual formula “the man and the writer” the two, waging a constant battle, suffer the same fate.

Although it was peace-time, the Petrashevsky group were tried by military tribunal. The “plot of ideas” was no less frightening for the government than a plot of action. Dostoyevsky, together with twenty other young men, was sentenced to death. The prosecutor general appealed to the Emperor for a commutement of the death sentence for other punishments (in the case of Dostoyevsky to eight years of hard labour). Nicholas I wrote against his name: “To four years, and a private in the army afterwards.”

The Russian Emperor did not want any martyr Still, the criminals themselves and their comrades who were still at large had to be given an object lesson. And so the Emperor took upon himself the functions of a theatrical producer and staged an execution.

On the morning of December 22nd, 1849, the prisoners were marched to the Semenovsky parade-ground and had the death sentence read out to them. The men then had white burial robes put on them, and those of them who belonged to the nobility each had a sword (filed beforehand) broken over his head. Petrashevsky and two of his comrades were tied to posts dug into the ground; the firing squad took aim with their rifles; a drumbeat exploded into the frosty air.

Dostoyevsky stood in the second trio, he had no more than five minutes left to live. He was to remember those minutes for ever.

The prisoners were untied from the posts, ordered back to the scaffold and had their new sentences read out to them. Petrashevsky died in Siberia, and Dostoyevsky returned to St. Petersburg ten years later.

“Brother, my dear brother! It’s all over!” he wrote on the evening of the mock execution. “My vital spirits have never before seethed in me so copiously and healthily as now. Will my body endure, I do not know.”

He did not know yet that his body was no longer merely the dwelling place of his spirit but already a part of it: a few years later his “holy” sickness would bring this unbearable truth home to him.

“Brother! I swear to you that I shall not lose hope and will preserve my spirit and my heart in purity. I shall be re-born for the better. That’s my only hope, my only consolation.”

And he was true to his promise.

Very few accounts of his four years of hard labour in Omsk Fortress have survived. Dostoyevsky’s Notes from the Dead House (1861-1862) is the fullest we have.

“…Those four years I regard as a time when I was buried alive and interred in a coffin… It was suffering, inexpressible, interminable…” he wrote later. All those four years he wore leg chains (the Emperor rejected the appeal to remove them before time). For the writer it was a school of life which introduced him to such depths of existence which he never even suspected before. “And here, too, among the criminals I singled out people at last … there are some strong, splendid characters…”

Hard-labour convicts were strictly forbidden to write, but even so Dostoyevsky managed to make notes of proverbs, sayings, and examples of folk expressions, known to us as his “Siberian Note-Book”.

It is popularly believed that it was during his hard-labour term in Siberia that Dostoyevsky’s change of heart began, and his convictions underwent a regeneration. This thought calls for clarification.

Was Dostoyevsky a revolutionary? His actions, in any case, leave no room for doubt on this score. But on the other hand we have no reason to doubt his sincerity either when in the evidence he gave at his trial (and later) he spoke with disapproval about the prospects of a “Russian revolt”.

- Description

- Additional information

Description

Description

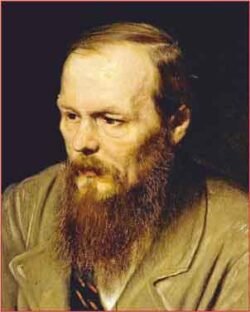

The name of the great Russian writer Fyodor Dostoyevsky (1821-1881) is mainly associated with his philosophically psychological novels which brought him world-wide fame Crime and Punishment, The Idiot, The Raw Youth, The Possessed, and The Karamazov Brothers.

And yet one of his most interesting novels is The Gambler (1866) about the all-devouring passion for gambling which defeats even the gambler’s passion for the woman whose love he has been trying to win for a long time. As usual, Dostoyevsky studied the nature of man here in all its aspects. This is what he wrote about the hero of this novel: “He is a gambler, and not a simple gambler… He is a poet in his own way, but he himself is ashamed of this poetry, for he deeply feels its unworthiness, albeit this craving for risk does ennoble him in his own eyes.”

The Insulted and Humiliated is one of the most popular and readable novels by Dostoyevsky. Lev Tolstoy’s assessment of the book is well known… “I recently read The Insulted and Humiliated and was very moved.”

The Novel is the embodiment of one of the author’s favourite themes of his creative work. Dostoyevsky counterposes the moral fortitude and the spirit of love and brotherhood, which unite the poor, to the egoism and dissoluteness of the aristocracy, which separate people and alienate them from each other.

The novel and particularly the character of the narrator, Ivan Petrovich, synthesises many personal facts of the author’s life.

In 1988 RADUGA begun the publication in English translation of selected works of Fyodor Dostoyevsky (1821-1881), one of the greatest Russian writers and thinkers whose whole life was dedicated to finding the answers to the most burning questions of human existence which continue to engage the minds of people to this day. RADUGA published Dostoyevsky’s novels and stories fully representative of his genius.

The novel Poor People (1845) was the first book published by the young writer, and it started him on his way to world-wide fame. Dostoyevsky’s concern for the “little man” crushed by need, whose inner world he tried to fathom and understand, is already clearly manifested in all his early short stories included in the first book to come out: “Mister Prokharchin” (1846), “The Landlady” (1847), “A Faint Heart” (1848), “An Honest Thief” (1848), and “White Nights” (1849)-the most poetic story in Russian literature.

“…human beings remain human everywhere. And in the four years of hard labour in Siberia I at last came to distinguish human beings among the thieves. Will you believe me: there are deep, strong, beautiful characters, and what a joy it was to discover gold beneath the rough, hard shell… How many popular types, characters have I brought with me out of penal servitude! I have lived in the closest possible contact with them and consequently, it seems, know them pretty well… What a wonderful people. Altogether no time has been lost to me if I have come to know if not Russia, then the Russian people well, and so well as perhaps not many know them.”

From a letter Dostoyevsky, wrote to his brother Mikhail, dated 22 February, 1854

“…How much youth was interred here between these walls for no purpose, what great forces had perished in here to no avail. This has got to be said, all of it, openly: the people here were extraordinary people. Perhaps they possessed the most talents and the greatest strength of all our people. Yet this great strength perished here, and perished unnaturally, unlawfully, irrevocably. Who is to blame for this?”

Dostoyevsky, “Notes from the Dead House”

“In our literature Dostoyevsky holds a place quite apart in the profundity of his conception and the breadth of the moral problems he elaborates in his novels. He not only recognizes the conclusiveness of his contemporary society’s interests, but even goes further, and enters the sphere of pre-sentiments and previsions which are the aim of remote, not immediate, seekings of humankind…”

Mikhail Saltykov-Shchedrin

“I put my soul, body and blood into it … in the novel there are two huge typical characters which took me five years to create and which (in my opinion) are perfectly finished; they are fully Russian characters, but until now they have been poorly outlined in Russian literature.”

Fyodor Dostoyevsky, on his novel, Stepanchikovo and Its Inhabitants

“I have seen and know that people can be wonderful and happy without losing the ability to live on this earth. I do not want to and cannot believe that evil is the normal state of people.”

Fyodor Dostoyevsky, A Funny Man’s Dream

“With Dostoyevsky one never asks: what did he want to say? Wherever one opens him, one sees quite clearly his thought, feeling, intention, perception, everything that had accumulated within him and that filled him to overflowing, demanding an outlet.”

Lev Tolstoy

A genius ranking with Shakespeare, Dante, Goethe and Tolstoy-that is how Maxim Gorky, the renowned writer, described Fyodor Dostoyevsky (1821-1881).

The novel Crime and Punishment (1865-1866) was conceived by Dostoyevsky during his exile in Siberia. Its theme was focal in all his writings: the fate of nine-tenths of mankind morally crushed by the society of his times.

“I was enchanted by Crime and Punishment,” wrote Romain Rolland, one of its first foreign readers. “I am prepared to place this novel on a par with Tolstoy’s War and Peace. The two are equally great. War and Peace is boundless life, an ocean of souls… Crime and Punishment is a storm raging within a single soul…”

“With all the force of his soul and talent, with all the efforts of his thought and qualms of conscience, Dostoyevsky reacted to the complex and burning problems of a tragic time, when money, violence and cynicism turned people into a means of achieving a soulless and meaningless aim: profits to win power, and power for the sake of profits.

“As in his lifetime, his writings tell us the story of man’s spiritual rebellion, the turmoil within his soul in search of a way out. It will rather choose destruction than consent to become a commodity.”

— Konstantin Fedin (1892-1977), Soviet novelist

Additional information

Additional information

| Weight | N/A |

|---|---|

| Dimensions | N/A |

| Product Options / Binding Type |

Related Products

-

-42%

Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product pageQuick ViewFiction / कपोल -कल्पित, Hard Bound / सजिल्द, New Releases / नवीनतम, Novel / उपन्यास, Panchayat / Village Milieu / Gramin / पंचायत / ग्रामीण परिप्रेक्ष्य, Tribal Literature / आदिवासी साहित्य, Women Discourse / Stri Vimarsh / स्त्री विमर्श

Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product pageQuick ViewFiction / कपोल -कल्पित, Hard Bound / सजिल्द, New Releases / नवीनतम, Novel / उपन्यास, Panchayat / Village Milieu / Gramin / पंचायत / ग्रामीण परिप्रेक्ष्य, Tribal Literature / आदिवासी साहित्य, Women Discourse / Stri Vimarsh / स्त्री विमर्शBin Dyodi ka Ghar (Part-3) (Novel) / बिन ड्योढ़ी का घर (भाग-3) (उपन्यास) – Tribal Hindi Upanyas

₹599.00Original price was: ₹599.00.₹350.00Current price is: ₹350.00. -

-20%

Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product pageQuick ViewBhojpuri / भोजपुरी, Fiction / कपोल -कल्पित, Hard Bound / सजिल्द, New Releases / नवीनतम, Novel / उपन्यास, Panchayat / Village Milieu / Gramin / पंचायत / ग्रामीण परिप्रेक्ष्य, Paperback / पेपरबैक, Stories / Kahani / कहानी

Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product pageQuick ViewBhojpuri / भोजपुरी, Fiction / कपोल -कल्पित, Hard Bound / सजिल्द, New Releases / नवीनतम, Novel / उपन्यास, Panchayat / Village Milieu / Gramin / पंचायत / ग्रामीण परिप्रेक्ष्य, Paperback / पेपरबैक, Stories / Kahani / कहानीGirne Wala Bunglow aur anya Katha Sahitya

₹144.00 – ₹240.00

गिरने वाला बंगला एवं अन्य कथा साहित्य -

Criticism Aalochana / आलोचना, Novel / उपन्यास, Paperback / पेपरबैक, Sanchayan / Essays / Compilation संचयन / निबंध / संकलन (Anthology), Women Discourse / Stri Vimarsh / स्त्री विमर्श

Nikash par Tatsam (Rajee Seth kai upanyas par Ekagra) निकष पर तत्सम (राजी सेठ के उपन्यास पर एकाग्र)

₹250.00Original price was: ₹250.00.₹225.00Current price is: ₹225.00. -

Sale

Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product pageQuick ViewArt and Culture / Kala avam Sanskriti / कला एवं संस्कृति, Fiction / कपोल -कल्पित, Hard Bound / सजिल्द, New Releases / नवीनतम, North East ka Sahitya / उत्तर पूर्व का सााहित्य, Novel / उपन्यास, Panchayat / Village Milieu / Gramin / पंचायत / ग्रामीण परिप्रेक्ष्य, Paperback / पेपरबैक, Top Selling, Translation (from Indian Languages) / भारतीय भाषाओं से अनुदित, Tribal Literature / आदिवासी साहित्य

Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product pageQuick ViewArt and Culture / Kala avam Sanskriti / कला एवं संस्कृति, Fiction / कपोल -कल्पित, Hard Bound / सजिल्द, New Releases / नवीनतम, North East ka Sahitya / उत्तर पूर्व का सााहित्य, Novel / उपन्यास, Panchayat / Village Milieu / Gramin / पंचायत / ग्रामीण परिप्रेक्ष्य, Paperback / पेपरबैक, Top Selling, Translation (from Indian Languages) / भारतीय भाषाओं से अनुदित, Tribal Literature / आदिवासी साहित्यVarsha Devi ka Gatha Geet वर्षा देवी का गाथागीत (असम की जनजातियों पर आधारित उपन्याय, मूल असमिया से हिन्दी में)

₹150.00 – ₹330.00